The 20 Best Books of 2021

[image description: a vintage gray typewriter with a piece of white paper coming out of the top that says “2021.”]

[post contains an affiliate link in case you want any of these books]

It seems like every time I make a “best of [year] list I think, “where does the time go?!”

I also think, “but I can’t do that yet!” because it’s not yet December 31st as I’m writing this and I am currently reading books that could, in theory, be some of the best books I read in this calendar year. It’s an imprecise science, but here we are.

For starters, I read way fewer books in 2021 than I have in previous years. But I also wrote more books this year than I have in previous years (one whole book, Midwest Shreds; most of the draft of a novel; an outline for a music book that I’m not ready to share yet; and making headway on a book about my favorite restaurant that I’m also not quite ready to share). So I’m trying to cut myself some slack. For the past couple of years I’ve read between 150 and 175 books and this year I read 125. I realize 125 is still a lot, but when you compare that to my previous reading record, 25-50 books fewer is a significant chunk.

I’ll also admit that I’ve had a hard time keeping up with my reading goals for the past couple of years, which have focused more on reading specific books (namely for research purposes for things I want to write) than the number of books I want to read. These days my minimum goal is 100 books a year because I’ve built up the habits that allow me to do so without significantly changing my habits. I thought I’d have a ton of time this past year to really make some headway on my memoir, but it turns out that being a full-time writer means writing things for which you are being paid. Who would’ve thought!

I jest and I love what I do. But this memoir has vexed me since 2016 and is still very much a work in progress. Maybe one day I’ll have it together enough to share with you. I say all this because, considering my less-than-stellar track record, I’m not planning to set specific reading goals this year.

I’m still going to be tracking my reading, though! Even though I think I know myself, something always surprises me. Here’s how 2021’s numbers stack up. I read…

27 books by Black authors

2 books by Latinx authors (yikes! so low!)

19 books by Asian authors

6 books by other authors of color (more on this below)

20 books by LGBTQ+ authors

3 books by nonbinary authors (more on this below)

81 books by women authors

and 24 books published by small presses

Some of these authors have overlapping identities, so for example an author who is a Black queer woman would show up as three separate tallies on my lists. Again, it’s an imprecise science.

The “other authors of color” is for Arab/Middle Eastern authors who self-identify as people of color. Arabs can be Black, brown, or white, so I typically don’t include them in the other categories unless they self-identify as POC.

I also deliberately broke out nonbinary authors from the LGBTQ+ category because gender presentation ≠ sexuality, despite how often the two are conflated. And as a nonbinary person, I also just wanted to track that separately to better see it for myself.

And before I dive into my list, I want to specify that I read new releases and backlist titles throughout the year, so the books listed here are not necessarily new releases from 2021. Some are, some are not. And while I normally rank the books from 1st to 20th place, I had a hell of a time deciding which book should get first this year, so my list is in no particular order. These are all books I loved and would happily read again.

Without further ado…

The Secret Lives of Church Ladies by Deesha Philyaw

The Secret Lives of Church Ladies explores the raw and tender places where black women and girls dare to follow their desires and pursue a momentary reprieve from being good. The nine stories in this collection feature four generations of characters grappling with who they want to be in the world, caught as they are between the church's double standards and their own needs and passions. With their secret longings, new love, and forbidden affairs, these church ladies are as seductive as they want to be, as vulnerable as they need to be, as unfaithful and unrepentant as they care to be, and as free as they deserve to be.

Before I read The Secret Lives of Church Ladies, I don’t think I’d ever read a short story collection where I loved every single story. It was so fantastic that I read it in an afternoon and frequently tell people who don’t think they like short stories to check it out. They always thank me later.

Blacktop Wasteland by S. A. Cosby

Beauregard "Bug" Montage: husband, father, honest car mechanic. But he was once known - from North Carolina to the beaches of Florida - as the best getaway driver on the East Coast. Just like his father, who disappeared many years ago.

After a series of financial calamities (worsened by the racial prejudices of the small town he lives in) Bug reluctantly takes part in a daring diamond heist to solve his money troubles - and to go straight once and for all. However, when it goes horrifically wrong, he's sucked into a grimy underworld which threatens everything, and everyone, he holds dear . . .

Confession: I LOVE the Fast & Furious movies. I love them all! They’re a total sausage fest and I can’t get enough. Tokyo Drift is my favorite, but if I catch any of them on TV (and they’re played with alarming frequency on several networks) I drop what I’m doing and settle in for a nostalgic thrill ride. Blacktop Wasteland is like a literary Fast & Furious, but BETTER. Everything about the reading experience is fun and compelling.

The Death of Vivek Oji by Akwaeke Emezi

Raised by a distant father and an understanding but overprotective mother, Vivek suffers disorienting blackouts, moments of disconnection between self and surroundings. As adolescence gives way to adulthood, Vivek finds solace in friendships with the warm, boisterous daughters of the Nigerwives, foreign-born women married to Nigerian men.

But Vivek’s closest bond is with Osita, the worldly, high-spirited cousin whose teasing confidence masks a guarded private life. As their relationship deepens—and Osita struggles to understand Vivek’s escalating crisis—the mystery gives way to a heart-stopping act of violence in a moment of exhilarating freedom.

Propulsively readable, teeming with unforgettable characters, The Death of Vivek Oji is a novel of family and friendship that challenges expectations—a dramatic story of loss and transcendence that will move every reader.

This book made the list because, although fairly short, it takes you on a deep emotional journey that will have you crying by the end. Nothing about it is predictable. Every part of the story is bold and heartfelt.

Detransition, Baby by Torrey Peters

A whipsmart debut about three women—transgender and cisgender—whose lives collide after an unexpected pregnancy forces them to confront their deepest desires around gender, motherhood, and sex.

Reese almost had it all: a loving relationship with Amy, an apartment in New York City, a job she didn't hate. She had scraped together what previous generations of trans women could only dream of: a life of mundane, bourgeois comforts. The only thing missing was a child. But then her girlfriend, Amy, detransitioned and became Ames, and everything fell apart. Now Reese is caught in a self-destructive pattern: avoiding her loneliness by sleeping with married men.

Ames isn't happy either. He thought detransitioning to live as a man would make life easier, but that decision cost him his relationship with Reese—and losing her meant losing his only family. Even though their romance is over, he longs to find a way back to her. When Ames's boss and lover, Katrina, reveals that she's pregnant with his baby—and that she's not sure whether she wants to keep it—Ames wonders if this is the chance he's been waiting for. Could the three of them form some kind of unconventional family—and raise the baby together?

This provocative debut is about what happens at the emotional, messy, vulnerable corners of womanhood that platitudes and good intentions can't reach. Torrey Peters brilliantly and fearlessly navigates the most dangerous taboos around gender, sex, and relationships, gifting us a thrillingly original, witty, and deeply moving novel.

I saw a reviewer (I think for the NYT?) say that Detransition, Baby is a gift to trans women and the rest of us should feel lucky that we get to enjoy it, and I second that. I’ve never read anything like it––it’s the most original piece of fiction I’ve ever read. I’ve read several books by trans authors, but most of them have been nonfiction and now I’m eager to read more fiction by brilliant trans authors. A truly unforgettable work.

Little Eyes by Samanta Schweblin

A visionary novel about the collision of technology and play, horror and humanity, from a master of the spine-tingling tale.

They've infiltrated homes in Hong Kong, shops in Vancouver, the streets of Senegal, town squares of Oaxaca, schools in Tel Aviv, bedrooms in Ohio. They're following you. They're everywhere now. They're us.

In Samanta Schweblin's wildly imaginative new novel, Little Eyes, "kentukis" have gone viral across the globe. They're little mechanical stuffed animals that have cameras for eyes, wheels for feet, and are connected to an anonymous global server. Owners of kentukis have the eyes of a stranger in their home and a cute squeaking pet following them; or you can be the kentuki and voyeuristically spend time in someone else's life, controlling the creature with a few keystrokes. Through kentukis, a jaded Croatian hustler stumbles into a massive criminal enterprise and saves a life in Brazil, a lonely old woman in Peru becomes fascinated with a young woman and her louche lover in Germany, and a motherless child in Antigua finds a new virtual family and experiences snow for the first time in Norway.

These creatures can reveal the beauty of connection between farflung souls - but they also expose the ugly humanity of our increasingly linked world. Trusting strangers can lead to unexpected love and marvelous adventure, but what happens when the kentukis pave the way for unimaginable terror?

How do you capture things as vast and amoral as money and the internet in fiction? Everyone has a different relationship to them and they have been vehicles for life-changing good as well as unspeakable terror. That’s exactly what Samanta Schweblin did in this novel. We see a diverse array of characters––all colors, all ages, from all around the world, rich and poor, health and sick––experiencing a technology that has become ubiquitous and that some use for good while others use for evil. I love the structure of the novel as well as what it says about our society; providing the kind of insights that fiction is so adept at.

I Will Die In a Foreign Land by Kalani Pickhart

A visionary novel about the collision of technology and play, horror and humanity, from a master of the spine-tingling tale.

They've infiltrated homes in Hong Kong, shops in Vancouver, the streets of Senegal, town squares of Oaxaca, schools in Tel Aviv, bedrooms in Ohio. They're following you. They're everywhere now. They're us.

In Samanta Schweblin's wildly imaginative new novel, Little Eyes, "kentukis" have gone viral across the globe. They're little mechanical stuffed animals that have cameras for eyes, wheels for feet, and are connected to an anonymous global server. Owners of kentukis have the eyes of a stranger in their home and a cute squeaking pet following them; or you can be the kentuki and voyeuristically spend time in someone else's life, controlling the creature with a few keystrokes. Through kentukis, a jaded Croatian hustler stumbles into a massive criminal enterprise and saves a life in Brazil, a lonely old woman in Peru becomes fascinated with a young woman and her louche lover in Germany, and a motherless child in Antigua finds a new virtual family and experiences snow for the first time in Norway.

These creatures can reveal the beauty of connection between farflung souls - but they also expose the ugly humanity of our increasingly linked world. Trusting strangers can lead to unexpected love and marvelous adventure, but what happens when the kentukis pave the way for unimaginable terror?

This book is mind-blowing in the best way. I loved this book so much that I wrote a full review here.

The Stepping Off Place by Cameron Kelly Rosenblum

From debut author Cameron Kelly Rosenblum comes a stunning teen novel that tackles love, grief, and mental health as one girl must process her friend’s death and ultimately learn how to stand in her own light. Perfect for fans of All the Bright Places and We Were Liars.

It’s the summer before senior year. Reid is in the thick of Scofield High’s in-crowd thanks to her best friend, Hattie, who has been her social oxygen since middle school.

But summer is when Hattie goes to her family’s Maine island home. Instead of sitting inside for eight weeks, waiting for her to return, Reid and their friend, Sam, enter into a pact—to live it up, one party at a time.

But days before Hattie is due home, Reid finds out the shocking news that Hattie has died by suicide. Driven by a desperate need to understand what went wrong, Reid searches for answers.

In doing so, she uncovers painful secrets about the person she thought she knew better than herself. And the truth will force Reid to reexamine everything.

I might not have heard of this book if it hadn’t been for my freelance gig reviewing books for the Kenyon College alumni magazine. Every quarter my editor drops a stack of books on my porch (which is just delightful) and I’m introduced to the works of the college’s brilliant alumni. This book called to me and I’m SO glad I read it! I stayed up until 5am finishing it and cried at the end. It’ll rip your heart open, then delicately sew it back together. It’s such a pure and wholesome exploration of grief and how we can never truly know a person.

Work Won't Love You Back: How Devotion to Our Jobs Keeps Us Exploited, Exhausted, and Alone by Sarah Jaffe

A deeply-reported examination of why "doing what you love" is a recipe for exploitation, creating a new tyranny of work in which we cheerily acquiesce to doing jobs that take over our lives.

You're told that if you "do what you love, you'll never work a day in your life." Whether it's working for "exposure" and "experience," or enduring poor treatment in the name of "being part of the family," all employees are pushed to make sacrifices for the privilege of being able to do what we love.

In Work Won't Love You Back, Sarah Jaffe, a preeminent voice on labor, inequality, and social movements, examines this "labor of love" myth -- the idea that certain work is not really work, and therefore should be done out of passion instead of pay. Told through the lives and experiences of workers in various industries -- from the unpaid intern, to the overworked nurse, to the nonprofit worker and even the professional athlete -- Jaffe reveals how all of us have been tricked into buying into a new tyranny of work.

As Jaffe argues, understanding the trap of the labor of love will empower us to work less and demand what our work is worth. And once freed from those binds, we can finally figure out what actually gives us joy, pleasure, and satisfaction.

I think everyone should read this book, especially now in the midst of this pandemic-induced labor movement. Whether you have a day job you love, a day job you hate, are over-employed, underemployed, freelance, part-time, or whatever, this book will clarify so many asinine beliefs we have around work and how those beliefs don’t actually serve us. My only regret is that I didn’t read it sooner.

My Year Abroad by Chang-rae Lee

From the award-winning author of Native Speaker and On Such a Full Sea, an exuberant, provocative story about a young American life transformed by an unusual Asian adventure - and about the human capacities for pleasure, pain, and connection.

Tiller is an average American college student with a good heart but minimal aspirations. Pong Lou is a larger-than-life, wildly creative Chinese American entrepreneur who sees something intriguing in Tiller beyond his bored exterior and takes him under his wing. When Pong brings him along on a boisterous trip across Asia, Tiller is catapulted from ordinary young man to talented protégé, and pulled into a series of ever more extreme and eye-opening experiences that transform his view of the world, of Pong, and of himself.

In the breathtaking, "precise, elliptical prose" that Chang-rae Lee is known for (The New York Times), the narrative alternates between Tiller's outlandish, mind-boggling year with Pong and the strange, riveting, emotionally complex domestic life that follows it, as Tiller processes what happened to him abroad and what it means for his future. Rich with commentary on Western attitudes, Eastern stereotypes, capitalism, global trade, mental health, parenthood, mentorship, and more, My Year Abroad is also an exploration of the surprising effects of cultural immersion—on a young American in Asia, on a Chinese man in America, and on an unlikely couple hiding out in the suburbs. Tinged at once with humor and darkness, electric with its accumulating surprises and suspense, My Year Abroad is a novel that only Chang-rae Lee could have written, and one that will be read and discussed for years to come.

This is one of those books that is weird and wonderful and it’s hard to describe what I liked about it or even why I couldn’t put it down. But I loved it and I couldn’t put it down. It’s full of adventure but not of the swashbuckling variety. It’s got unexpected romance, class issues, directionless youth, vengeful entrepreneurs, and other surprises.

Truly Like Lightning by David Duchovny

From the New York Times–bestselling author David Duchovny, an epic adventure that asks how we make sense of right and wrong in a world of extremes

For the past twenty years, Bronson Powers, former Hollywood stuntman and converted Mormon, has been homesteading deep in the uninhabited desert outside Joshua Tree with his three wives and ten children. Bronson and his wives, Yalulah, Mary, and Jackie, have been raising their family away from the corruption and evil of the modern world. Their insular existence—controversial, difficult, but Edenic—is upended when the ambitious young developer Maya Abbadessa stumbles upon their land. Hoping to make a profit, she crafts a wager with the family that sets in motion a deadly chain of events.

Maya, threatening to report the family to social services, convinces them to enter three of their children into a nearby public school. Bronson and his wives agree that if Maya can prove that the kids do better in town than in their desert oasis, they will sell her a chunk of their priceless plot of land. Suddenly confronted with all the complications of the twenty-first century that they tried to keep out of their lives, the Powerses must reckon with their lifestyle as they try to save it.

Truly Like Lightning, David Duchovny’s fourth novel, is a heartbreaking meditation on family, religion, sex, greed, human nature, and the vanishing environment of an ancient desert.

I’m normally leery of books written by celebrities. I have little to no interest in celebrity memoirs and have heard enough stories to believe 99% of them are ghostwritten anyway. And I generally could not care less how celebrities spend their time. The only non-book people I really fangirl over are My Chemical Romance and Lil Nas X… And David Duchovny. But here’s the thing: he’s actually really smart and has been writing fiction and poetry for a long time. I believe he wrote this novel and he did a damn good job at it.

The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America by Richard Rothstein

In this groundbreaking history of the modern American metropolis, Richard Rothstein, a leading authority on housing policy, explodes the myth that America’s cities came to be racially divided through de facto segregation—that is, through individual prejudices, income differences, or the actions of private institutions like banks and real estate agencies. Rather, The Color of Law incontrovertibly makes clear that it was de jure segregation—the laws and policy decisions passed by local, state, and federal governments—that actually promoted the discriminatory patterns that continue to this day.

Through extraordinary revelations and extensive research that Ta-Nehisi Coates has lauded as "brilliant" (The Atlantic), Rothstein comes to chronicle nothing less than an untold story that begins in the 1920s, showing how this process of de jure segregation began with explicit racial zoning, as millions of African Americans moved in a great historical migration from the south to the north.

As Jane Jacobs established in her classic The Death and Life of Great American Cities, it was the deeply flawed urban planning of the 1950s that created many of the impoverished neighborhoods we know. Now, Rothstein expands our understanding of this history, showing how government policies led to the creation of officially segregated public housing and the demolition of previously integrated neighborhoods. While urban areas rapidly deteriorated, the great American suburbanization of the post–World War II years was spurred on by federal subsidies for builders on the condition that no homes be sold to African Americans. Finally, Rothstein shows how police and prosecutors brutally upheld these standards by supporting violent resistance to black families in white neighborhoods.

The Fair Housing Act of 1968 prohibited future discrimination but did nothing to reverse residential patterns that had become deeply embedded. Yet recent outbursts of violence in cities like Baltimore, Ferguson, and Minneapolis show us precisely how the legacy of these earlier eras contributes to persistent racial unrest. “The American landscape will never look the same to readers of this important book” (Sherrilyn Ifill, president of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund), as Rothstein’s invaluable examination shows that only by relearning this history can we finally pave the way for the nation to remedy its unconstitutional past.

This book will change everything you think you know about housing, generational wealth, and race in America, even in purportedly liberal cities that pride themselves on their progressiveness. I learned how deeply entrenched racism is in all forms of housing, particularly home ownership and land covenants. The Color of Law should be required reading for humanity (at least in the US).

A Darker Shade of Magic by V. E. Schwab

Kell is one of the last Antari—magicians with a rare, coveted ability to travel between parallel Londons; Red, Grey, White, and, once upon a time, Black.

Kell was raised in Arnes—Red London—and officially serves the Maresh Empire as an ambassador, traveling between the frequent bloody regime changes in White London and the court of George III in the dullest of Londons, the one without any magic left to see.

Unofficially, Kell is a smuggler, servicing people willing to pay for even the smallest glimpses of a world they'll never see. It's a defiant hobby with dangerous consequences, which Kell is now seeing firsthand.

After an exchange goes awry, Kell escapes to Grey London and runs into Delilah Bard, a cut-purse with lofty aspirations. She first robs him, then saves him from a deadly enemy, and finally forces Kell to spirit her to another world for a proper adventure.

Now perilous magic is afoot, and treachery lurks at every turn. To save all of the worlds, they'll first need to stay alive.

I don’t read a ton of fantasy, but I was totally engrossed in the Shades of Magic series! I read the whole trilogy lightning fast, even though they’re not short books. I was completely enthralled and for a long while afterward had no desire to return to “real world” reading. Magic is the best escape!

The Final Revival of Opal and Nev by Dawnie Walton

An electrifying novel about the meteoric rise of an iconic interracial rock duo in the 1970s, their sensational breakup, and the dark secrets unearthed when they try to reunite decades later for one last tour.

Opal is a fiercely independent young woman pushing against the grain in her style and attitude, Afro-punk before that term existed. Coming of age in Detroit, she can’t imagine settling for a 9-to-5 job—despite her unusual looks, Opal believes she can be a star. So when the aspiring British singer/songwriter Neville Charles discovers her at a bar’s amateur night, she takes him up on his offer to make rock music together for the fledgling Rivington Records.

In early seventies New York City, just as she’s finding her niche as part of a flamboyant and funky creative scene, a rival band signed to her label brandishes a Confederate flag at a promotional concert. Opal’s bold protest and the violence that ensues set off a chain of events that will not only change the lives of those she loves, but also be a deadly reminder that repercussions are always harsher for women, especially black women, who dare to speak their truth.

Decades later, as Opal considers a 2016 reunion with Nev, music journalist S. Sunny Shelton seizes the chance to curate an oral history about her idols. Sunny thought she knew most of the stories leading up to the cult duo’s most politicized chapter. But as her interviews dig deeper, a nasty new allegation from an unexpected source threatens to blow up everything.

Provocative and chilling, The Final Revival of Opal & Nev features a backup chorus of unforgettable voices, a heroine the likes of which we’ve not seen in storytelling, and a daring structure, and introduces a bold new voice in contemporary fiction.

Weirdly, a rarely read books about actual musicians, but I love a fictional band. Opal & Nev was everything I could have hoped for. This novel reads like a whirlwind and is satisfying in every way. It’s a quick romp of joy and a blessed escape from reality. I think part of what draws me to books like this is humans, by their nature, are nosy and love drama to some degree but at least when it’s a fictional musician you don’t have to feel bad about listening to it like you would a problematic musician in real life. I’m also continually surprised at the creative ways people find to write about music, even when you can’t actually hear it. A truly gifted music writer will make you think you can.

The Inheritance of Orquídea Divina by Zoraida Córdova

The Montoyas are used to a life without explanations. They know better than to ask why the pantry never seems to run low or empty, or why their matriarch won’t ever leave their home in Four Rivers—even for graduations, weddings, or baptisms. But when Orquídea Divina invites them to her funeral and to collect their inheritance, they hope to learn the secrets that she has held onto so tightly their whole lives. Instead, Orquídea is transformed, leaving them with more questions than answers.

Seven years later, her gifts have manifested in different ways for Marimar, Rey, and Tatinelly’s daughter, Rhiannon, granting them unexpected blessings. But soon, a hidden figure begins to tear through their family tree, picking them off one by one as it seeks to destroy Orquídea’s line. Determined to save what’s left of their family and uncover the truth behind their inheritance, the four descendants travel to Ecuador—to the place where Orquídea buried her secrets and broken promises and never looked back.

I love the magical realism in Latinx literature and this novel does not disappoint! The family dynamic is so well captured, the magical elements are beautifully done, and the themes of memory and inheritance are captivating. I wanted to spend more time with the Divina family and learn more of their mystical secrets. Fingers crossed there’s a sequel!

Gentrifier: A Memoir by Anne Elizabeth Moore

Taking on the thorny ethics of owning and selling property as a white woman in a majority Black city and a majority Bangladeshi neighborhood with both intelligence and humor, this memoir brings a new perspective to a Detroit that finds itself perpetually on the brink of revitalization.

In 2016, a Detroit arts organization grants writer and artist Anne Elizabeth Moore a free house--a room of her own, à la Virginia Woolf--in Detroit's majority-Bangladeshi "Banglatown." Accompanied by her cats, Moore moves to the bungalow in her new city where she gardens, befriends the neighborhood youth, and grows to intimately understand civic collapse and community solidarity. When the troubled history of her prize house comes to light, Moore finds her life destabilized by the aftershocks of the housing crisis and governmental corruption.

This is also a memoir of art, gender, work, and survival. Moore writes into the gaps of Woolf's declaration that "a woman must have money and a room of one's own if she is to write"; what if this woman were queer and living with chronic illness, as Moore is, or a South Asian immigrant, like Moore's neighbors? And what if her primary coping mechanism was jokes?

Part investigation, part comedy of a vexing city, and part love letter to girlhood, Gentrifier examines capitalism, property ownership, and whiteness, asking if we can ever really win when violence and profit are inextricably linked with victory.

I loved this memoir so much! I wrote a full review here.

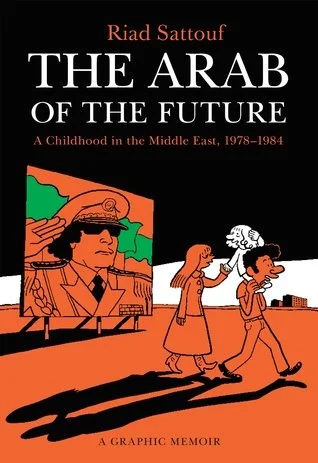

The Arab of the Future: A Childhood in the Middle East, 1978-1984: A Graphic Memoir by Riad Sattouf

The Arab of the Future, the #1 French best-seller, tells the unforgettable story of Riad Sattouf's childhood, spent in the shadows of 3 dictators—Muammar Gaddafi, Hafez al-Assad, and his father

In striking, virtuoso graphic style that captures both the immediacy of childhood and the fervor of political idealism, Riad Sattouf recounts his nomadic childhood growing up in rural France, Gaddafi's Libya, and Assad's Syria--but always under the roof of his father, a Syrian Pan-Arabist who drags his family along in his pursuit of grandiose dreams for the Arab nation.

Riad, delicate and wide-eyed, follows in the trail of his mismatched parents; his mother, a bookish French student, is as modest as his father is flamboyant. Venturing first to the Great Socialist People's Libyan Arab State and then joining the family tribe in Homs, Syria, they hold fast to the vision of the paradise that always lies just around the corner. And hold they do, though food is scarce, children kill dogs for sport, and with locks banned, the Sattoufs come home one day to discover another family occupying their apartment. The ultimate outsider, Riad, with his flowing blond hair, is called the ultimate insult… Jewish. And in no time at all, his father has come up with yet another grand plan, moving from building a new people to building his own great palace.

Brimming with life and dark humor, The Arab of the Future reveals the truth and texture of one eccentric family in an absurd Middle East, and also introduces a master cartoonist in a work destined to stand alongside Maus and Persepolis.

If you want to learn about Middle Eastern culture and politics, this book is pretty insightful. It’s also one big WHAT THE FUCK after another. I think I read three-quarters of this graphic memoir with my mouth hanging open. I loved this first in the series so much, I read installments two, three, and four as well. I’m impatiently awaiting for the fifth installment to be translated into English from French.

Low Country: A Southern Memoir by J. Nicole Jones

The Glass Castle meets Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil in this incandescent debut memoir of one family's changing fortunes in the Low Country of South Carolina, a tale inseparable from the region's storms and shipwrecks, ghosts and folklore.

J. Nicole Jones is the only daughter of a prominent South Carolina family, a family that grew rich building the hotels and seafood restaurants that draw tourists to Myrtle Beach. But at home, she is surrounded by violence and capriciousness: a grandfather who beats his wife, a barman father who dreams of being a country music star. At one time, Jones's parents can barely afford groceries; at another, her volatile grandfather presents her with a fur coat.

After a girlhood of extreme wealth and deep debt, of ghosts and folklore, of cruel men and unwanted spectacle, Jones finds herself face to face with an explosive possibility concerning her long-abused grandmother that she can neither speak nor shake. And through the lens of her own family's catastrophes and triumphs, Jones pays homage to the landscapes and legends of her childhood home, a region haunted by its history: Eliza Pinckney cultivates indigo, Blackbeard ransacks the coast, and the Gray Man paces the beach, warning of Hurricane Hazel.

I have a feeling Low Country will become classic Southern literature canon in time. It captures the dichotomy of the South so perfectly: extreme wealth and rampant poverty, untouched landscapes and overdeveloped beacons of tourism, Southern hospitality and deep, dark cruelty––and through it all, fantastical stories and folklore galore. I thoroughly enjoyed this book and wrote a full review here.

The People in the Trees by Hanya Yanagihara

In 1950, a young doctor called Norton Perina signs on with the anthropologist Paul Tallent for an expedition to the remote Micronesian island of Ivu'ivu in search of a rumored lost tribe. They succeed, finding not only that tribe but also a group of forest dwellers they dub "The Dreamers," who turn out to be fantastically long-lived but progressively more senile. Perina suspects the source of their longevity is a hard-to-find turtle; unable to resist the possibility of eternal life, he kills one and smuggles some meat back to the States. He scientifically proves his thesis, earning worldwide fame and the Nobel Prize, but he soon discovers that its miraculous property comes at a terrible price. As things quickly spiral out of his control, his own demons take hold, with devastating personal consequences.

This novel is enduringly relevant since the discussion about “is it cancel culture or is it accountability?” doesn’t seem to be going away. (Hint: it’s accountability.) I chose this novel for one of my book clubs and it proved to be perfect for generating thought-provoking discussions about the greater good, one’s legacy, the trolley problem, and how we as a society memorialize smart and talented people who are actually terrible humans.

The Binding by Bridget Collins

Books are dangerous things in Collins's alternate universe, a place vaguely reminiscent of 19th-century England. It's a world in which people visit book binders to rid themselves of painful or treacherous memories. Once their stories have been told and are bound between the pages of a book, the slate is wiped clean and their memories lose the power to hurt or haunt them.

After having suffered some sort of mental collapse and no longer able to keep up with his farm chores, Emmett Farmer is sent to the workshop of one such binder to live and work as her apprentice. Leaving behind home and family, Emmett slowly regains his health while learning the binding trade. He is forbidden to enter the locked room where books are stored, so he spends many months marbling end pages, tooling leather book covers, and gilding edges. But his curiosity is piqued by the people who come and go from the inner sanctum, and the arrival of the lordly Lucian Darnay, with whom he senses a connection, changes everything.

Just when I thought yet another novel about books couldn’t surprise me, this one blew me away. It’s a slow burn that sears on every page and is absolutely worth every word! This novel is simultaneously fresh and nostalgic.

Razorblade Tears by S. A. Cosby

A Black father. A white father. Two murdered sons. A quest for vengeance.

Ike Randolph has been out of jail for fifteen years, with not so much as a speeding ticket in all that time. But a Black man with cops at the door knows to be afraid.

The last thing he expects to hear is that his son Isiah has been murdered, along with Isiah’s white husband, Derek. Ike had never fully accepted his son but is devastated by his loss.

Derek’s father Buddy Lee was almost as ashamed of Derek for being gay as Derek was ashamed his father was a criminal. Buddy Lee still has contacts in the underworld, though, and he wants to know who killed his boy.

Ike and Buddy Lee, two ex-cons with little else in common other than a criminal past and a love for their dead sons, band together in their desperate desire for revenge. In their quest to do better for their sons in death than they did in life, hardened men Ike and Buddy Lee will confront their own prejudices about their sons and each other, as they rain down vengeance upon those who hurt their boys.

Provocative and fast-paced, S. A. Cosby's Razorblade Tears is a story of bloody retribution, heartfelt change - and maybe even redemption.

This is a first! (I think.) Two books by the same author made by “best of” list! Normally I group series together but only mention the first one. However, both of the S.A. Cosby novels I mentioned are set in different worlds and have different characters, so it didn’t make sense to lump them together, especially when I loved them for different reasons. Razorblade Tears has a redemptive arc as the fathers learn how to be better people through the course of hunting down their sons’ murderers and it’s so beautifully done. It’s not hit-you-over-the-head moralistic, but it did inspire me to believe that even the people who seem least likely to change have that capacity if they’re willing to let love in and do the work.

So there you have it! My 20 favorite books that I read in 2021.

If you like the sound of any of these books and would like to own them, I’d appreciate it if you’d buy them using my Bookshop link. Bookshop is an Amazon alternative that supports indie bookstores and blogs like mine. I’m grateful for the support!