Meet the Real-Life Indiana Jones of Medieval Manuscripts

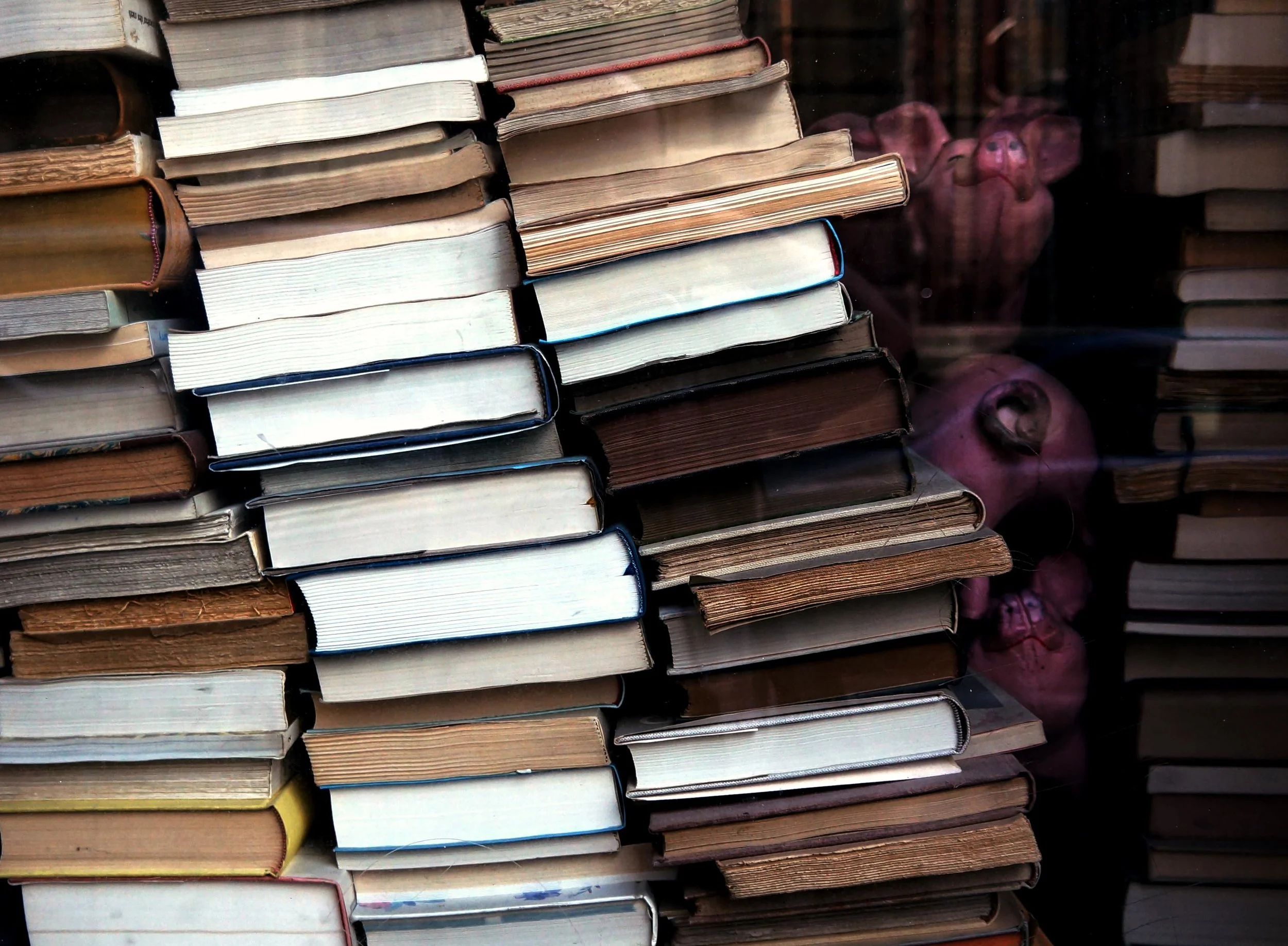

[image description: a page from an illuminated manuscript from the Medieval period. This page pre-dates the printing press, so it’s painted by hand, often using precious metals like gold and silver in the ink.]

I always assumed I’d take an interest in antiquarian books when I was older and had more disposable income. (Then again, that’s never guaranteed and might not even be feasible for Millennials, but I can hope.) I also assumed that books from the 1800s, which is my particular interest, would be extremely expensive. I’m happy to report that I was wrong on both accounts!

I recently celebrated my 31st birthday and treated myself to a couple of books from the 1800s, the cheapest being $21 and the most expensive being $60. Sure, there are some 1800s books that are several hundred or several thousand dollars apiece, though I’m not in the market for those. Given this fairly recent interest, I decided to join The Aldus Society, which is a local antiquarian book enthusiasts group in town.

They normally meet at the Thurber House, the home and museum dedicated to James Thurber in downtown Columbus, though due to the pandemic meetings have been virtual. I attended my first meeting recently and am hooked! The guy who spoke is basically the real-life Indiana Jones of Medieval manuscripts.

The speaker was David Gura, who is the Curator of Ancient and Medieval Manuscripts in the Hesburgh Library at the University of Notre Dame. Admittedly, I think Medieval books are cool but they’re not my particular area of collecting interest. In addition to being extremely rare, the likelihood of finding a Medieval book for $60 or less, which is my budget for this project right now, is 0%.

But unfortunately, there are antiquarian book enthusiasts like me with budget constraints that are most attracted to Medieval manuscripts. And their willingness to buy individual pages of illuminated manuscripts for $500 to $5,000 a pop when an entire book might cost $125,000 or more has led some antiquarian book dealers to unethical practice in selling.

Biblioclasty is the act of destroying books and it turns out that a number of antiquarian book dealers who sell Medieval manuscripts are biblioclasts. They’ll acquire an intact Medieval book then dismantle it page by page to sell the pages individually since selling individual pages is more profitable.

I know what you’re thinking because it’s the same thing I was thinking: How is that ethical?! Isn’t that illegal?! Biblioclasty is unethical, especially since these are irreplaceable books from 600+ years ago. There is a code of ethics for antiquarian book dealers, though the ones who practice biblioclasty choose not to abide by it. As far as legality, it’s apparently legal to destroy books in this manner.

The problem for scholars is that the individual pages or leaves from books lose meaning when they’re out of context with the rest of the book. That’s why when David Gura identified an illuminated manuscript that he wanted for the library’s collection and realized the pages had been sold individually, he set about tracking them down.

That, of course, is easier said than done. The book Gura wants is a 15th-century Breton Book of Hours. The Book of Hours was a Christian devotional popular in the Middle Ages. The particular copy Gura wanted was the customized personal prayerbook of a wealthy woman in western France from around 1450. The intact book was sold at a Sotheby’s auction in 2011 to an anonymous buyer in Germany who then broke the book to sell the pages individually. Gura became aware of the book when the pages began appearing on eBay.

This begs the question of who is buying these individual pages and do they know what they’re doing? It turns out that a lot of the people buying them just like them because they’re pretty and want to hang a piece of history on their wall. Most don’t realize that by buying individual pages they’re funding and encouraging biblioclasty. Gura has been reaching out to the buyers one by one on eBay and trying to educate them about the unethical practices in antiquarian bookselling and trying to convince them to sell the manuscript pages to the university so they can be used as research.

To date, Gura has been extremely successful. Of the 129 pages known to exist in this particular volume, he’s recovered 92 of them from places as far-flung as Germany and Japan and several countries in between. There are some he doesn’t know the location of and other pages he knows to exist and who has them, but the owners don’t want to sell.

Not all antiquarian booksellers who sell individual pages are biblioclasts, though. Antique books are, well, old and sometimes pages fall out. That’s normal. Or if the book is in terrible, unreadable condition but there are individual pages that can be saved, that’s obviously better than throwing out the entire book. Sometimes booksellers can even recover the materials of booksellers who were biblioclasts and sell the pages, even though the new owner bookseller didn’t themselves cut up the pages. The problem is specifically with the booksellers who buy antique, culturally significant books with the intention of cutting them up to sell the pages individually.

As simple as it might seem, identifying those unethical sellers is a challenge. For example, an antiquarian bookseller might say they don’t break books, but if a book is already in fragments or missing pages due to its age, then they can decide it’s fair game for biblioclasty since they didn’t do the initial breaking.

Some dealers will also, infuriatingly, put their dealer mark on the pages. Dealer marks are written in pencil, directly on the manuscript page, and can be anything from a particular symbol to a series of numbers or letters, to the price written a certain way. Dealer marks show the provenance of the pages––whose hands did this page pass through before it got where it is?

Interestingly, when asked if Gura removes the dealer marks once he acquires the pages and if he plans to have the book rebound if he’s able to buy all the pages, he said no. Gura said this is because the story of the book is not what the book used to be, it’s what the book has become. To rebind the book or erase the marks that show its provenance would artificialize its story.

For someone who deals with the effects of biblioclasts regularly, Gura is also more hopeful than I expected. When I asked how many complete, unbroken illuminated manuscripts he thought might be out there that have yet to appear in the marketplace, I expected him to say a hundred or fewer. Instead, he said probably thousands. He said that’s because the Book of Hours was extremely popular and lots of private collectors have them; that pieces will resurface that scholars had no idea were out there. He said you see this a lot with the children of World War II veterans who are getting older and they’re parting with things that were looted or acquired during the war and selling them off.

While I doubt Gura would call his work swashbuckling, he’s about the closest thing I’ve ever heard of to a real-life Indiana Jones since the Monuments Men. I learned a lot from his talk and you can follow David Gura on Twitter to learn more about his talks and work.